A Rhapsodist of Motorcars

By Roger Boylan

05.07.2008

I’m a writer, and I’ve always liked cars–or should that be “but I’ve always liked cars”? Creative artists, as honorary members of the romanticized struggling classes, have been presumed–almost required–to be Luddites, antagonistic to such symbols of swinish capitalism as mere machines. How often has one heard the bien-pensant dismissing the subject of, say, cars, with an airy “Oh but it’s just a car,” or “But I don’t care about cars”? Note how many eco-exhibitionists, modern-day heirs to the Marxist-Bohemian mantle, drive as their symbols of class hideous old beaters that belch clouds of pollution into the globally-warming atmosphere. Their animus toward motorized vehicles, especially SUVs, is legendary.

I’m a writer, and I’ve always liked cars–or should that be “but I’ve always liked cars”? Creative artists, as honorary members of the romanticized struggling classes, have been presumed–almost required–to be Luddites, antagonistic to such symbols of swinish capitalism as mere machines. How often has one heard the bien-pensant dismissing the subject of, say, cars, with an airy “Oh but it’s just a car,” or “But I don’t care about cars”? Note how many eco-exhibitionists, modern-day heirs to the Marxist-Bohemian mantle, drive as their symbols of class hideous old beaters that belch clouds of pollution into the globally-warming atmosphere. Their animus toward motorized vehicles, especially SUVs, is legendary.

So it’s a relief to come across a celebrated writer who loved cars and enjoyed being behind the wheel; and, one is tempted to say, what a writer, what a wheel! I refer to Rudyard Kipling, one of the pioneers of motoring, and his Rolls-Royce Phantom I. “Mr. Kipling,” growled a contemporary curmudgeon, W. L. Alden, “has long been addicted to the motor car. I say it with pain and disbelief, for the motor car is to my mind the most detestable of inventions.”

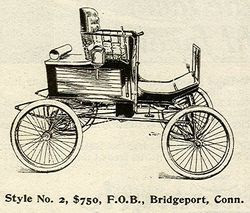

In 1902, the famous author of the Jungle Book, Kim, and Captains Courageous, went house-hunting in the south of England with Carrie, his American wife. They drove down in Kipling’s first car, a steam-powered American Locomobile whose sole attraction must have been (in clement weather) the experience of motoring in the open air. Its flaws included incredible slowness, unreliability, deafening noise, and a noxious smell.

In 1902, the famous author of the Jungle Book, Kim, and Captains Courageous, went house-hunting in the south of England with Carrie, his American wife. They drove down in Kipling’s first car, a steam-powered American Locomobile whose sole attraction must have been (in clement weather) the experience of motoring in the open air. Its flaws included incredible slowness, unreliability, deafening noise, and a noxious smell.

Fortunately, the Locomobile held up long enough to take the Kiplings from London to the northeastern corner of Sussex, where they came upon, and fell in love with, Bateman’s, a handsome Jacobean (17th-century) country house that later became the setting for Kipling’s story collection Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906). Flush with Rudyard’s earnings, they bought it on the spot.

Fortunately, the Locomobile held up long enough to take the Kiplings from London to the northeastern corner of Sussex, where they came upon, and fell in love with, Bateman’s, a handsome Jacobean (17th-century) country house that later became the setting for Kipling’s story collection Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906). Flush with Rudyard’s earnings, they bought it on the spot.

But on each subsequent visit to Bateman’s, the wretched Locomobile broke down, so it was soon dispatched to Locomobile heaven (a very small place) and replaced with an elegant 2.4 liter, air cooled Lanchester.

But on each subsequent visit to Bateman’s, the wretched Locomobile broke down, so it was soon dispatched to Locomobile heaven (a very small place) and replaced with an elegant 2.4 liter, air cooled Lanchester.

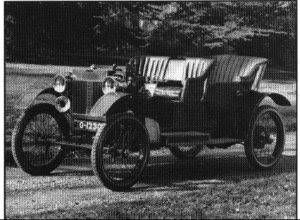

Lanchesters were among the first gasoline-driven four-wheel cars in Britain and became known for their innovative engineering; indeed, Autocar magazine estimates that 18 of the 36 primary features of modern cars were developed by Lanchester. Kipling owned or borrowed several Lanchesters over the years, including a Ten, the Jaguar XJ of its day (a fitting comparison, since Jaguar later bought out Lanchester). He used them primarily for motoring holidays in France, his favorite country after his own.

Lanchesters were among the first gasoline-driven four-wheel cars in Britain and became known for their innovative engineering; indeed, Autocar magazine estimates that 18 of the 36 primary features of modern cars were developed by Lanchester. Kipling owned or borrowed several Lanchesters over the years, including a Ten, the Jaguar XJ of its day (a fitting comparison, since Jaguar later bought out Lanchester). He used them primarily for motoring holidays in France, his favorite country after his own.

Kipling subsequently became a motoring correspondent for the Daily Mail, an unusual situation for a Nobel Prize winner; a rough equivalent today might be, say, Harold Pinter doing a car column for the Independent. But he loved the job, and welcomed the distraction that cars provide from life’s ironies and agonies. (He needed such distraction, especially after losing his son John in the trenches in 1916.) He became what A. N. Wilson, the novelist and scholar, calls “a rhapsodist of motorcars.”

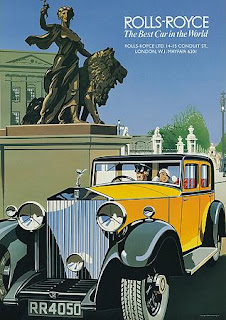

The 1920s were the post-Lanchester era for Kipling; he gave his heart to Rolls-Royce, “the only car I can afford,” he said, referring to the marque’s already-legendary reliability and solid construction. As part of his duties as motoring correspondent, he drove new Rollses over to France and down to the Rivera where, in the Roaring Twenties, there were plenty of buyers: 224 by mid-decade, including many luminaries of the smart sets chronicled by the likes of Somerset Maugham and Scott Fitzgerald.

The 1920s were the post-Lanchester era for Kipling; he gave his heart to Rolls-Royce, “the only car I can afford,” he said, referring to the marque’s already-legendary reliability and solid construction. As part of his duties as motoring correspondent, he drove new Rollses over to France and down to the Rivera where, in the Roaring Twenties, there were plenty of buyers: 224 by mid-decade, including many luminaries of the smart sets chronicled by the likes of Somerset Maugham and Scott Fitzgerald.

In the garage at Bateman’s, now administered by the National Trust, Britain’s heritage conservation group, sits Kipling’s last, and favorite, Rolls: the blue 1928 Phantom I that he doted on and drove along England’s country lanes and the tree-lined highways of France until his death in 1936.

Early in his motoring career Kipling, who was an inexhaustible fount of productivity, wrote a series of poems on automotive themes that were also parodies of literary styles through the ages and collected them under the title The Muse Among the Motors. In this wry pseudo-Wordworthian verse, a dying chauffeur contemplates his death.

Wheel me gently to the garage, since my car and I must part—

No more for me the record and the run.

That cursèd left-hand cylinder the doctors call my heart

Is pinking past redemption—I am done!

They’ll never strike a mixture that’ll help me pull my load.

My gears are stripped—I cannot set my brakes.

I am entered for the finals down the timeless untimed Road

To the Maker of the makers of all makes!

Kipling once said that the motor car was a time-machine in which centuries slid by like milestones, revealing “a land of stupefying marvels and mysteries.” I’ll try to hold that thought on tomorrow’s commute.

COPYRIGHT Full Metal Autos – All Rights Reserved